Body of Color

Naima Lowe’s Installation ‘Ropes, Pinks’ Uncoils Trauma in Pursuit of Black Freedom

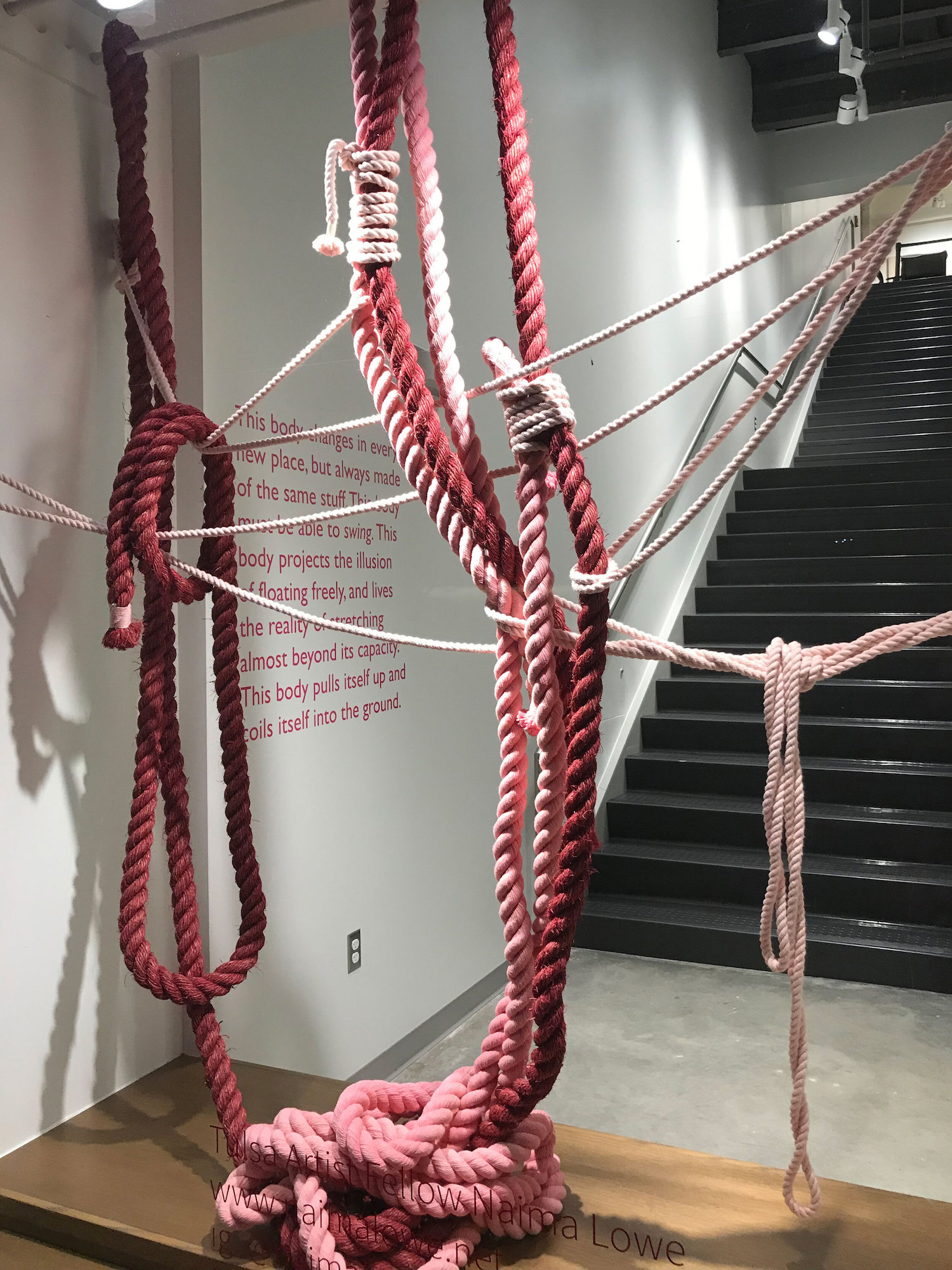

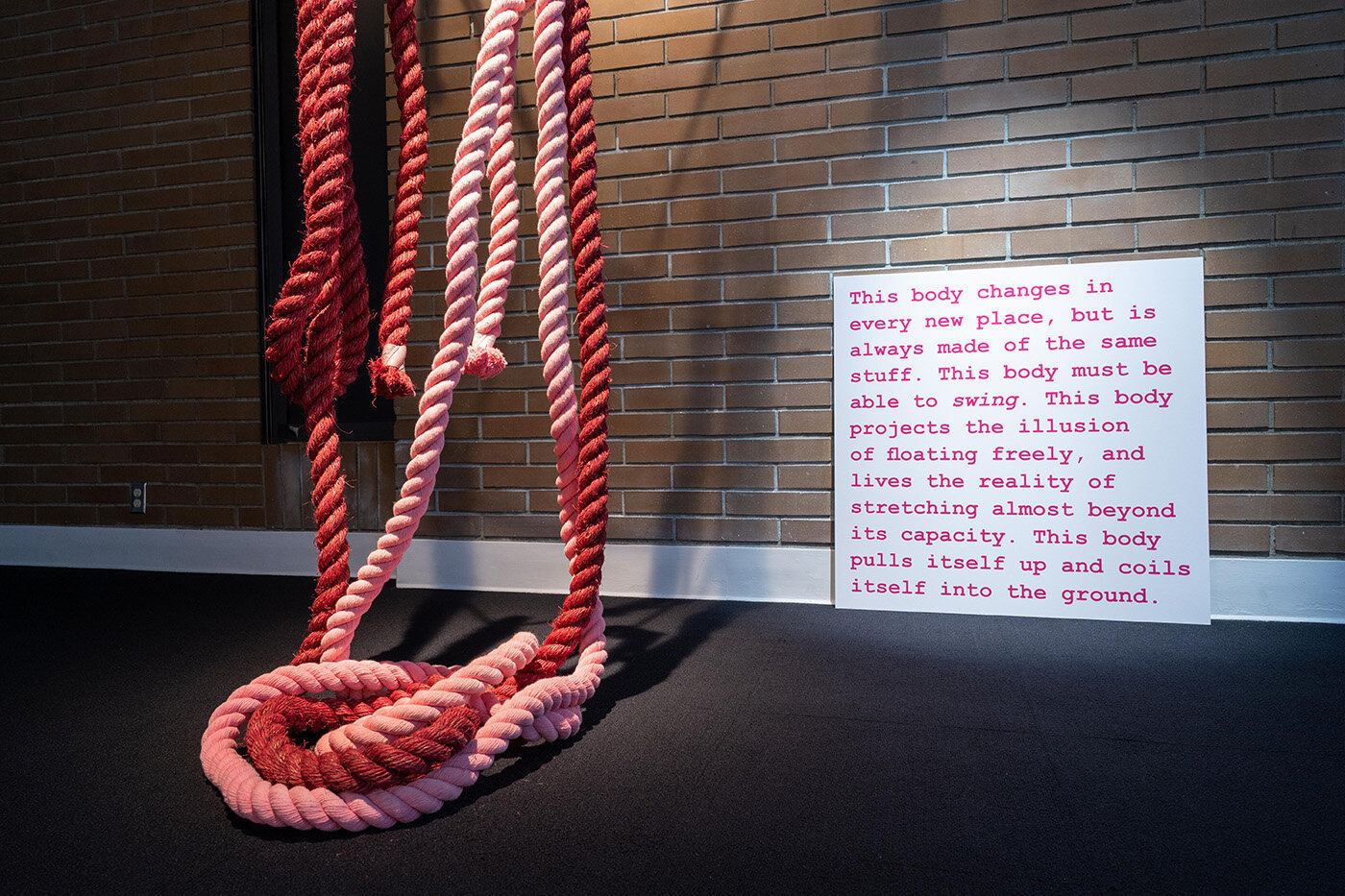

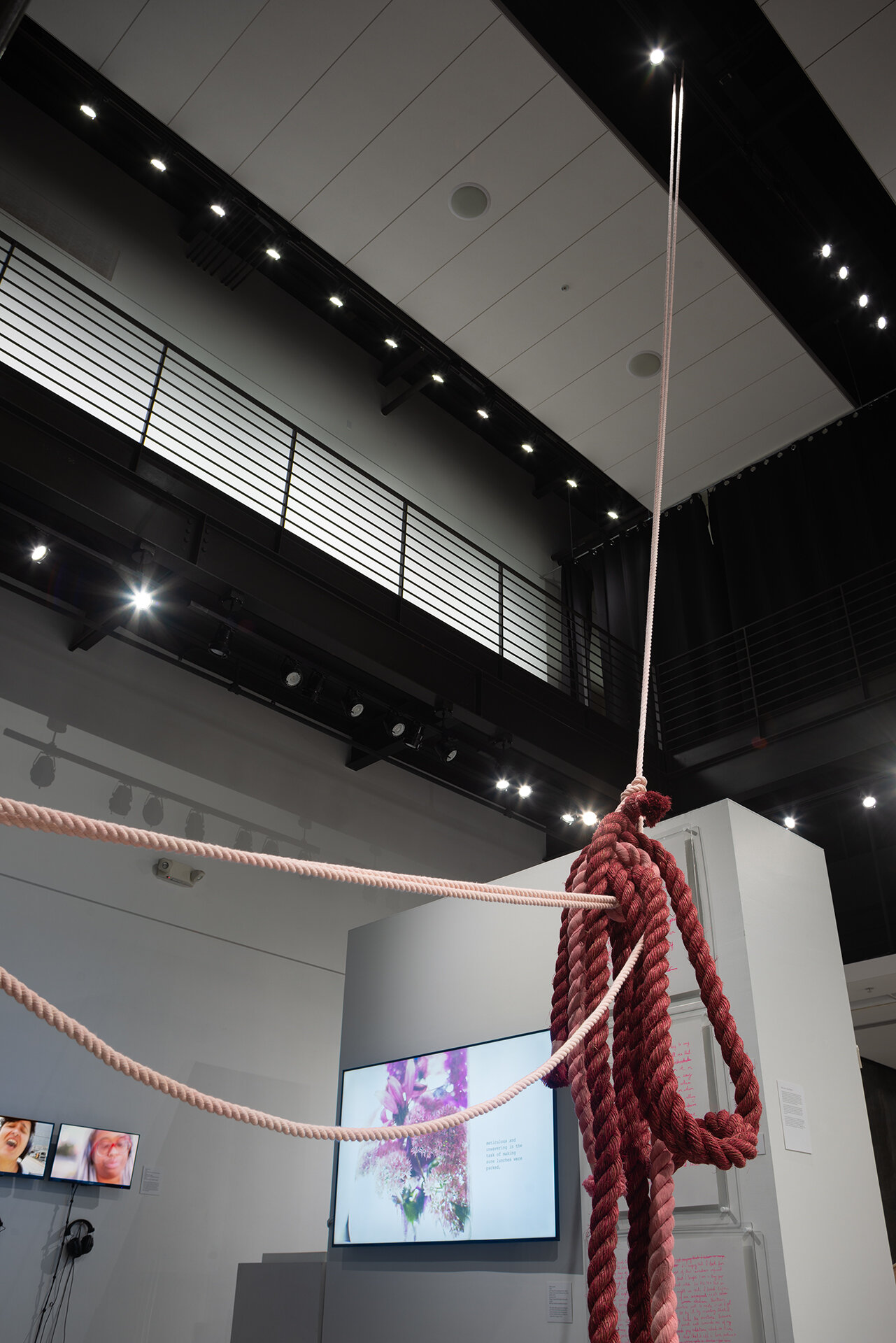

Consisting of three lengths of cotton and hemp rope of varying thicknesses—200 feet in all—dyed in shades of pink, “Ropes, Pinks” is an installation work by artist Naima Lowe. This “body” changes each time it is installed, adapting to and challenging the space where it finds itself attempting to be at home. In so doing, it twines itself around and among questions of racist horror, gender, intimacy, vulnerability, history, and love.

Lowe has exhibited videos, performances, and installations throughout the United States and created the independent art and design imprint Trial and Error during the pandemic. She comes from a long line of Black makers (musicians, fashion designers, farm laborers) and has left two coveted art positions after being targeted by what she names as pervasive racism. She spoke with editor-at-large Minal Hajratwala via Zoom about her work, her family’s artistic legacy, and why “Ropes, Pinks” is an act of self-portraiture.

I’m curious about the origin story of this work, “Ropes, Pinks,” as an installation that also has an improvisation quality to it, since it changes each time you hang it. How did it come about?

It emerged from the same energy as my abstract painting, and it has a relationship to performance and theater, which is a big part of my background. I was at a residency where I was determined to write this essay about my experience at Evergreen State College, trying to reckon with having been silenced. I was dealing with anxiety, frustration, sadness, and the fear that if I put anything out publicly I would become a target again.

It struck me how much I felt like I had to be so logical and so perfect and do that thing as a Black woman where, in order for someone to hear you, you have to do all these mental backflips. The color was a way for me to express what was also going on, which was me screaming and crying. I was imagining being inside a color. Pink was this central theme that kept coming up, and I thought, how is anybody going to take this seriously—this crinkly, sloppy pinkness?

At that residency, my father came and visited, because we’re working on some music projects together. I had this whole convoluted explanation for the paintings, and he looked at me and was like, “I think you just got to do it. Whatever this is, commit to it and try.”

One of the things that I’ve learned from him as a jazz musician is that it’s important to focus on bringing the tools that you have to the improvisational moment with as much commitment as you can. Ultimately I decided that improvisation was going to be part of the conceit of the work, that it would actually change each time, within a set of parameters: that it would hang, that it would swing, that it would seem like it was sort of pulling and pushing, that it would move in more than one direction.

A dear friend and artist, Aisha Harrison, suggested this exercise where you personify a piece of work and have a conversation with it and ask it what it means. Through that I started to embrace the explicit kind of association with lynching, and of pink with gender and queerness, even though that wasn’t where I was originally coming from, and also embrace the way that it can be lots of different sort of elements at once.

I imagine it coiled up like a snake in your studio, and I noticed that you often install it in conjunction with video. What has surprised you through the different installations? Does this “body” continue to communicate with you?

I am consistently surprised by the various ways that I can create a sense of literal tension in the ropes without adding in other elements. It speaks to the relationship between vulnerability and strength. One way I think about this work is that it’s like the insides of a body: It’s like intestines, it’s like viscera.

It can exist on its own but also as part of a larger narrative. The video that is most often installed nearby is this autobiographical meditation on the origins of my name, which is this very small, intimate thing: water, flowers, hand, Black music, and obviously, the pink. When I’ve held open studios, people had such an intense physical reaction to how pink my studio was. For some it was a magnetic draw, and for some it would be almost a physical revulsion, like “gross,” and they would walk right out.

What I’ve been going toward is this idea that pink is the inverse of black, or kind of the flip side—it’s part of it. Black people in this country have so much deep sensitivity. We know this: People who have been harmed, people who have experienced trauma are very sensitive. And various kinds of reactivity or frustration or capacities for beauty and creativity are functions of sensitivity.

The expectation that we be calm and erudite and quote-unquote civilized—those expectations are about other people’s fears. If you actually grappled with how awful it is to have treated people like property for so long, you’d have to deal with all of this anger and pain and sadness and frustration and confusion. And so instead, you try to tamp it down—from everybody, and in particular from Black folks.

Pink is an expression of that sensitivity, the power of that, and how scary it is. These guts are just always showing, just out and exposed to the world. How painful that is, that level of being exposed and sensitive. And how powerful it can be—to consistently be like a lightning rod.

I’m moved by the ways that you speak about your relationship with your father in your art, both in the video about your name and in the film about his experience as a journalist in 1967, being beaten by police while covering a protest in New Jersey. It’s amazing for a queer artist to have such a direct lineage that you can draw on. I wonder what you want to say about that?

I feel extremely lucky to have been raised by artists and around artists. I have as many hang-ups and anxieties and imposter syndrome as any artist, but there was never a point when I had to be convinced that this was a valid occupation and work. It was something that families, Black families, working class families, did. My father is an artist, but so was his mother, so was his father, and his grandfather. Art and teaching and ministry and community work all wove together as part of that lineage. My mother sews and designs clothing and quilts. My dad’s first wife, who I’m close with, is a poet. It is not unusual for me to call someone in my family for support and inspiration because they’re people who both know me but also know the creative questions that I’m trying to ask and the lineages that I swim in. They know the oppression and the violence and have a lot of experience of creating as an absolutely critical element of survival.

I have purposely designed projects to learn along with them. In this country, we were commodities. So we’re always going to be playing around with—and having a tension around—the way that our utterances are commodified. It’s always been a survival strategy on really practical levels, like, this is stuff we can do in order to make money.

But also it gave people opportunities to nourish themselves, to communicate with one another, to create opportunities for freedom making. Being able to dig into that has been such a blessing, including the parts of it that are just purely nerdy. One of my favorite things is when those groups of artists get together somewhat outside of, like, a white gaze, when we’re actually looking toward each other instead of outward, and get to just nerd out about music theory or film theory and the realities of how that touches our other experiences historically, culturally, whatever comes into play. We get to play. That is an incredible thing to have as a groundwork for how I was just brought into this world. My parents connected early on, through music, and I was named after [the John Coltrane] song for a reason.

A lot of the pink is also dedicated to him, because he’s actually spent an enormous amount of his life developing and creating a sort of sensitivity and nurturance in him that the world does its best to beat out of an adult Black man.

Send A Letter To the Editors