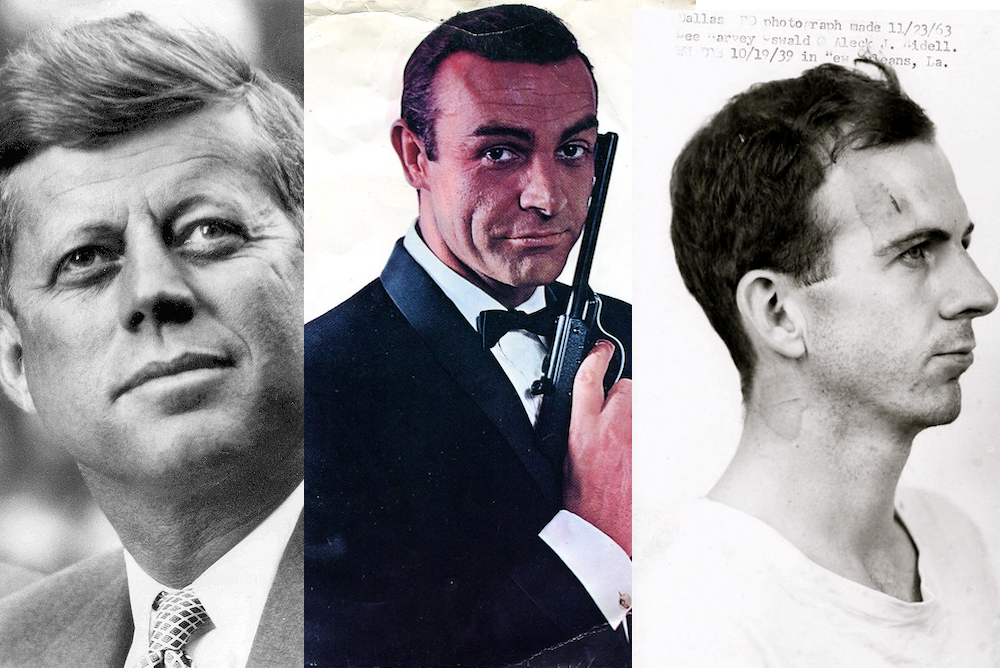

John F. Kennedy (left) and his assassin Lee Harvey Oswald (right) were very different people—but both enjoyed James Bond (center, as played by Sean Connery). Kennedy photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Bond photo courtesy of Johan Oomen/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED). Oswald photo courtesy of 00anders/Flickr (public domain).

President John F. Kennedy and Lee Harvey Oswald were both killed in Dallas on the same weekend in November 1963. They were men from distinctly opposed walks of life, and ended up being on opposite sides of a murder. But they also had things in common. Both were also given to hiding parts of themselves, and engaged in the kind of daring behavior exhibited by James Bond in Ian Fleming’s novels.

John F. Kennedy first read Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale while recovering from back surgery in 1954. When he became president and a reporter asked him to name his favorite books, he included Fleming’s From Russia, with Love. Sales of the novel skyrocketed.

In 1960, he invited the writer to his Georgetown home. “They talked foreign affairs,” reported the Washington Post, “with Fleming arguing that the United States could topple Fidel Castro by dropping pesos over Havana, together with leaflets reading ‘Compliments of the United States.’”

Conspiracy-meisters have claimed that that’s what the CIA actually did, but the record is not clear. One thing that did happen, according to the Post, is that CIA chief Allen Dulles (also a Bond fan) ordered 007-style gadgets such as exploding cigars and knife-tip shoes for his agents that were evidently deployed in Cuba; various accounts point to Castro as having been on the receiving end of an incendiary stogie.

But while Kennedy may have resembled Bond—handsome, debonair, and with a reputation for secret entanglements with mob boss girlfriends, colleagues’ wives, and Marilyn Monroe—it was Oswald who pulled off a Bond-style covert operation. Oswald’s own secret life is said to involve the Miami Cubans, the KGB, the CIA, Dallas oilmen, and the gay New Orleans underground. But in my view, his hidden life was not about allying with covert figures to carry out the greatest homicide of the 20th century, but how to advance beyond his meager circumstances and achieve fame and recognition. He and his mother were locked in a “conspiracy of one,” as I call it—a desperate campaign to matter. When opportunity presented itself on November 22, 1963, Oswald did not let it pass.

It was a lifetime in the making. As a boy, Oswald had a predilection for spying, going undercover, and tricking people. He loved “Let’s Pretend,” a popular radio show for children in which actors re-created classic tales before a live studio audience in Duluth, Minnesota. The show was broadcast nationwide every Saturday morning, and many parents of the era, including Oswald’s mother Marguerite, awaited the weekly airing, welcoming the de facto babysitter. Lee stayed glued to the radio at the designated time, and would act out the stories on his own for his older brothers throughout the week.

One of the reasons that Oswald escaped into fables was that his mother was given to melodrama and constantly sought attention. He spent a great deal of time at the library, especially in New Orleans, his birthplace. (A footnote to his fondness for libraries is that after he was killed, it turned out that a book he had checked out in Dallas was overdue.)

The records at the Napoleon branch of the New Orleans public library show that Lee was a regular in the stacks and had wide-ranging reading interests. Among the books he checked out in the months immediately preceding the assassination were the Bond novels Goldfinger, Thunderball, Moonraker, and From Russia, with Love.

He also borrowed Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage and William Manchester’s Portrait of a President, about Kennedy. Contrary to what many believe, Oswald actually admired the president. He kept a copy of Time magazine with J.F.K. on the cover on his coffee table in Fort Worth and harbored a desire for a part of the American Dream that for him was long foreclosed, but that Kennedy represented. Shortly after the birth of his first daughter, he told his wife that he hoped their next child was a boy: “Someday,” he said, “he could grow up to become President.”

Drawing on his diverse literary inspiration, Oswald made himself the star and director of dramatic scenes throughout his short life. These included violent bullying—often directed at his wife—and loud proclamations of his rights at the mention of any infraction.

His mother was his biggest fan, although her admiration was conditional. Privately, she was withholding and distant, but in public, whenever he was involved in an altercation or dispute, she was quick to utter the mantra of those who feel that they are perpetual victims. “My son did no such thing … he would never do that,” she would say to anyone who accused Lee of misbehavior. In the months and years following the assassination of the President, her proclamations on behalf of her son reached new heights. “Well, even if my son did kill J.F.K.,” she told reporters, “he’s a national hero because the President had Addison’s disease and Lee put him out of his misery. He should be buried in Arlington National Cemetery.”

Of course, that did not happen. Oswald was interred in Fort Worth–in “the middle class section,” as she made a point of saying proudly to a journalist. Years later, Marguerite was buried in a neighboring plot. For both, a dream had been fulfilled. Lee had finally won fame and recognition—and with it, the everlasting approval of Marguerite. Meanwhile, Marguerite, who had spent her life working menial jobs and feeling dismissed and disparaged, finally felt acknowledged. As the mother of the assassin, she courted and received reporters, basking in the spotlight that she had long desired.

J.F.K. screened a rough cut of From Russia, with Love, two days before he was killed—the last movie he’d see. He had been communicating privately in those final weeks with Russian premier Nikita Khrushchev, and the two men were approaching agreement on plans for total nuclear disarmament, according to reports that surfaced after the assassination.

But it was Oswald who knew a more intimate side of Russia. He had lived there as a defector, attending parties, dating women, and acquiring a beautiful Russian wife named Marina. He returned to the U.S. in June 1962 with Marina on his arm—and the copy of Time with J.F.K. on the cover that his mother had sent to him in Minsk.

Then, on the morning of November 22, 1963, Oswald embarked on his own spy-thriller operation. He picked up the rifle that he had been hiding in a friend’s garage and headed to work at the Texas School Book Depository. Shortly after noon, he whacked the president, and before long, he himself would enter the history books that he was packing up on the job.

“Even the highest tree,” Fleming wrote in From Russia, with Love, “has an axe at its foot.”

Send A Letter To the Editors